Check: brazilianopera.com

Brazil has a long tradition of opera.

The country was an important stop in the international circuit of opera companies. Maestro Arturo Toscanini, did his conducting début in the Theatro Municipal, Rio de Janeiro, then capital of the country. All major opera singers also toured the country as independent performers or as part of major productions.

Throughout the second monarchy and the early republican times (roughly 1850-1950), Rio was always an important stop for the international circuit of opera companies.

The emperor Pedro II, wanted to commission an opera from Richard Wagner, legend would have one believe that this could have been Tristan und Isolde. The scene was recently featured as part of another opera, by Brazilian director Gerald Thomas. It seem that his counselors dissuaded him of the idea. We know the Emperor enjoyed opera, he attended the première of The Ring Cycle at Bayreuth. At the hotel guestbook we can see his name with the word “Emperor” filled in on the “occupation” entry.

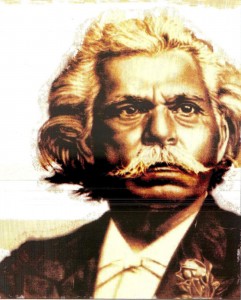

Yet the most remarkable contribution that the Emperor Pedro II gave to the world of opera was in the grant that he provided to a composer of extraordinary talent. A young man from a farm town who had fainted after the first time he played piano for the monarch. A boy of mixed race in a country that still depended on slavery for its economy. That boy was to become the most promising composer of operas in Italy in the time when Verdi was developing his mature style. That boy was Carlos Gomes.

Carlos Gomes – the successful savage

Opera was a big genre in Brazil up to the 50’s. The theaters were packed, there were many local production companies. All the major international stars toured through our main opera houses. Then something happened. Some say that Bossa Nova killed Opera in Brazil. Opera came to represent all that was to be avoided in European culture: the overblown dramatic stage, the easy emotional representation. Yet I believe that it remained latent as an undercurrent through much sophisticated Brazilian popular music.

The early samba song format is very influenced by the Italian aria, in melodic inflections and dramatic content, even in the singing style, until Tom Jobim and João Gilberto came along. The guitar player’s complaints about Elizete Cardoso‘s vibrato, on the recordings of the first bossa nova album ever, are a turning point in the history of Brazilian popular music. Bel canto was the main vocal style at the time and it made a lot of sense to distance ourselves from it. Bossa is samba with a chamber attitude, attention to detail and a distaste for dramatic bravado.

Carlos Gomes

We already had a tradition of opera composers. The greatest was Antonio Carlos Gomes – until proven contrary, he remains the greatest opera composer from all the Americas. In fact, he was the only non-European to be successful in loco, during the golden age of Italian opera. In any case, he was the first New World composer whose work was accepted in Europe.

Carlos Gomes was Brazilian, of mixed race. He was known to straighten his hair with an iron apparatus. He was a generation younger than Verdi, yet admired by the later and followed passionately by the Italian audience. We must remember that Leopold Mozart (the father) was only satisfied about the recognition of his son once they had been approved in Italy. Leopold feared and revered Italy, the motherland of classical music. He was only completely assured of the remarkable talent of his son after the boy had been acclaimed by the Italian masters.

Carlos Gomes was simply adored in Italy. Younger than Verdi, yet older than Puccini; at a certain time, between the première of his first few operas and their successful productions, he was the most beloved composer by the Italian audiences. Verdi is rumored to have been one of his admirers. A successful composer in a profitable market, Gomes became quickly rich, as soon as his first operas were staged in Europe. A man of humble origins, who had come from a small farming town, he feasted in this new-found wealth. Gomes built a palace in Milan, he called it Villa Brasil, with imported trees from the motherland, a greenhouse, huge statues from characters from his major hit “O Guarani”, many extravaganzas…and then he lost it all in a dry creative spell that lasted more than ten years.*

It seems that Carlos Gomes had issues with part of the inspired savage (il salvagio), that he had to play. He passed the exams at the Milan Conservatory and proved his worth to a great extent due to the success of his opera Il Guarani. The main character Peri became a cultural symbol in the intellectual discussion about the national identity that would take place later, in the first half of the XX century. The native Brazilian hero who saves his beloved Ceci from a flood was drawn will all the obvious European allusions to the idealized “noble savage”.

Carlos Gomes himself apparently struggled with this, as he would not write another opera with a Brazilian theme until Il Schiavo, later in his life. It was a time when audiences responded well to operas with an exotic setting. He wrote his music on the rules of the Italian market and he struggled with it; always fighting with his Italian librettists and destroying first acts of operas.

Gomez arrived in Italy as a young musician of humble origins and savage looks who wanted to learn from the Italian masters. He wanted to prove his valor in the same idiom of the European standards. Throughout Brazilian cultural history Carlos Gomes has been criticized and used as a symbol for the artist who wields to the European aesthetics and at the same time to ratify ethnic stereotypes.

Mario de Andrade, poet, musician and theorist, and author of the novel Macunaíma hat put forward the character that would provide a mythical counterpoint to the idealized Peri. He was the one who came to defend Carlos Gomes and Peri in a heated debate that is well documented in a recent book that reports on the perception of Carlos Gomes in Brazilian culture: “Carlos Gomes: Um Tema em Questão” by Lutero Rodrigues (Unesp 2011).

The music of Carlos Gomes is Italian in construct and orchestration, in the vocal idioms and harmonic architecture yet it is also full of very Brazilian melodious aspects that are so dear to our hearts. This melodic ingenuity had it conquer the heart of so many Italians and other contemporaries. His musical merit is unquestionable.

Il Guarany, Fosca, Lo Schiavo, or any other of his 12 operas, the are all very accomplished works. There are hidden gems, especially in his horn sections that bring to mind his upbringing as the son of the director of the local marching band. There are a lot of theatrical possibilities that can still be explored within Gomes music. Hi most famous work, Il Guarany, should be considered for the repertoire of any serious opera company, especially in the Americas. Not only for the cultural and historic value of these operas, but mostly for the beauty of the music. This main trilogy, could be appreciated even in cantata concert format.

Unfortunately we don’t really have a mature production from Carlos Gomes. Gomes was a perfectionist. He destroyed the manuscripts of some twenty first-acts, burning on impulse the labor of months of work on different operas, always struggling with the Italian librettists, always aiming at artistic excellence and perfection. Brahms, who also destroyed much of his work, had to come to terms with the ghost of Beethoven; Gomes had to deal with the living Verdi. More than that, he had to deal with the challenge of overcoming the prejudices of a racist culture.

He needed to prove that a composer of mixed blood from a remote rural town in the tropics could be as good a composer as the best in Europe, and even better. He proved his point, though he may have sacrificed much of his artistic impulses in a search for some unattainable idealized opera. This is a field where the lasting impression of a composer is dependent on a sizable output, it was a scene where a composer would need to be premiering new operas regularly and thus developing his skill. We can witness the musical and artistic development of Verdi and Puccini, both became better composers in their mature style. We can only imagine what all the manuscripts that Gomes burned would have sounded like, but his inner struggle is a testament to the time when he lived and to the power o an individual to overcome unfavorable conditions. A good biography is available by the novelist Rubem Fonseca: O Selvagem da Ópera.

Yet there’s something beautiful about the subtle tension between his music and the Italian words, especially in the moments when they really lock. Everything Gomes left is of high quality and should be considered for serious performance.

Villa Lobos also wrote a few operas. Magdalena is in English, Yerma has a Spanish libretto. Both composers had issues with being labeled ethnic, as if it would diminish the credit to their craft. Yet they also struggled to imprint the mark of the depth of their cultural origins, each in his own peculiar way.

…

Bossa Nova came when a historical change demanded an opposite aesthetic style. It was partly an affirmation that we shared the jazz lineage of popular music by a separate but parallel vein of cultural influences. It was also an affirmation of national identity that appropriated subtle sophisticated harmonic elements from expressionist classical music, while rejecting the exaggerations and dramatic excesses from the symphonic and operatic styles. Bossa Nova put samba in the concert hall, in a chamber environment. The high artistry of the style would make it internationally respected.

…

Anthropophagy

In the 1920’s, Brazilian modernists founded the Athropophagic Art Movement. The Art-Cannibalists. This concept is crucial to understand most Brazilian art since and much from before then. There is an inherent tension between absorbing the high art of the colonizer, rejecting it in essence but also creating something unique that proves the value of a culture that urges to prove its autonomy, but struggles to come to terms with its colonial heritage. In many ways Brazilian artists behave like a child or a teenager who still looks for approval from the father, yet wants this approval to be granted on one’s own terms. There is an inherent tension in our earning for our roots in Native and African cultures and the choice of elements to be absorbed from European high culture. In early Samba for example, there is an obvious passion to dive into the power of the African inherited drums, but also a melodic sophistication and harmonic discourse that stems from the classical European tradition, this is specially noticeable in the popular works of Chiquinha Gonzaga (Also remembered as an early feminist).

The concept of Cannibalism was essential to liberate our artists from this cursed struggle. We must remember the context in which cannibalism happened in tribal cultures, all over the new continent, from the extreme south of Latin America to the remote Islands of Hawaii. A practice that probably dates to a very remote time, an early practice in human unrecorded history.

In the European perception, the striking fact is the consumption of human meat, but that only speaks to the very surface of the inherent symbolism and complex system of values. Cannibalism was not meant to satisfy any nutritional needs, it was a ritual. A ritual to assimilate the qualities of the stranger, only brave warriors deserved to be eaten. But that is not all, first the stranger would be brought into the tribe, assimilated and women would dispute his company and bear his babies, his skills would be learned and evaluated. Only then one would be submitted to ritual sacrifice and consumption. A true warrior would prove bravery facing death. Apparently many Europeans who returned to tell the tales of the New World and to write books about the savages were just cowards who were not fully fit for the ritual and no one would want to eat them.

…

Chamber Bossa Nova

The Harmonic Development of Brazilian Song

If Villa Lobos brought Brazilian Popular music into the classic tradition, Tom Jobim brought Classical Music into the tradition of Brazilian Popular song.

Antonio Carlos Brasileiro Jobim was a fully trained classical composer, but he also picked up a lot from brazilian folk styles and other popular musicians. The roots for his harmonic style are in Chopin and Debussy, but also in Pixinguinha, João Pernambuco, Ernesto Nazareth, Villa Lobos. He also picked up a lot from his contemporaries, the guitar harmonies of Joao Gilberto and the piano of Joao Donato.

The influence of Jazz is not really as big as some may think. Of course he was familiar with Gershwin and Cole Porter and the American popular song certainly had a place in the shaping of the form. However, Jobim writes vocal music that stresses the dissonant intervals over the chord, the melody often lies on the Maj7th, even in simple songs like Vivo Sonhando and the Girl from Ipanema. Though that can be found in the interpretation style of some great early Jazz singers, it is not a compositional feature until later.

His most popular tune: “Garota de Ipanema” has a main theme that insists on the 9th, the M7 and the 6th of the I chord. It never touches the ˆ1, ˆ3, ˆ5, (to be fair there is a moment when it briefly touches the one, but as 7 of the ii chord) the anchor tones of pretty much any popular tune until then. In fact, the melody resolves on ˆ5 and it only stresses the ˆ1 of the main key when the tune actually modulates to the key of the Neapolitan. Then the ˆ1 becomes the M7 of the new key.

All these harmonies imply in a solid craftsmanship grounded in the works of the classic repertoire, though stylistically it is closely related to the subtle harmonic vocabulary of Chopin and Debussy. The second theme is a modulation that could fit at he exposition section of the standard sonata form, though the modulatory sequence is daring and oblique, where the sequence is harmonized in major than in minor and then up a second, as if to make an interval statement that connects the modulation pattern to the interval that dominates the first main theme. The second section often tricks the inexperienced musician. Yet, this is Jobim’s most popular radio friendly tune. Few people who were alive through the XX Century would fail to recognize the melody of “The Girl From Ipanema.

These features had been present in romantic music of the classic tradition, but in vocal popular music there is a question of emphasis that needs to be addressed. We are talking about a major commercial hit that competes with the Beatles in cheer number of recorded versions.

Of course Jobim was not just interested in writing an easy memorable song. Throughout his work there is an urge for musical depth, a certainty that bossa-nova could be high art. Jobim had already written two symphonies before he became a successful songwriter. He is unique among the Brazilian songwriting tradition in that he had a solid classic background. Yet he owes much to the high quality of the craft that had been established before he came along. I order to truly understand Jobim’s originality and contribution, we must dive deep into the music of Chiquinha Gonzaga, Ernesto Nazareth, Donga, Noel Rosa, Assis Valente, and deeper into the early religious melodies of different origins that have been preserved in the popular tradition.

…

The Brazilian Guitar

Both the Portuguese and the Spanish tradition has a taste for portable string instruments such as the guitar the cavaco, the lute, the mandolin. They took this passion to the new world. They probably inherited that from the six hundred years of Arabic rule. The ukalele is a Hawaian invention out of a native copy of the Portuguese cavaco, with a different tuning.

The guitar crossed the ocean to Brazil as a polular instrument, an instrument of peasants, of sailors. If we were to establish a parallel between the Brazilian social divide, it’s cultural Freudian relationship with the culture of the motherland, rejected and coveted, we could establish the intrumetation of this dialog with the guitar as the icon representing the working class. The guitar is an instrument that struggled for acceptance in the world of serious music. As such compositions of very early Brazilian guitar music shows aspects of counterpoint and structures of deliberate construction that signal this desire to prove the worth of this music to the local aristocracy.

It is interesting that this portable instrument of warm tones does not blend well in chamber ensembles and even less in opera houses. If we look closer into the guitar music of João Pernambuco we can hear these chromatic descents of diminished chords that may remind us of late romantic Chopin or Wagner. He was a man of humble origins, who is supposed to have though some guitar informally to Villa Lobos, in the outskirts of Rio. Later Villa returned the favor by digging a job in the conservatoire to the aging composer. Villa Lobos also expanded the legacy by writing a set of guitar compositions that gave the classic guitar a repertoire of unprecedented historic proportions.

Villa Lobos is the composer who sets the ground for the development of the bossa nova guitar style and the subsequent technical and harmonic advancements of the Brazilian popular guitar.

In many ways Brazilian popular music developed in a parallel path to North American Jazz, yet many contrasting differences. Of course both counties share a common history of colonization and an economy based on slave trade and the cultural merges and conflicts that may surface. In both traditions there are musicians of great technical sophistication that seems to challenge the divide between popular and fully notated music. It is not an accident that many Brazilian standards were incorporated into the jazz repertoire. Musicians from both traditions have been listening and paying attention to each other since radio and recordings were made available, and even before through cruises and tours of small groups in both directions. New Oleans jazz was introduced to Rio as early as 1912. Yet the harmonic and aesthetic development of Brazilian Popular Music and Jazz are quite distinct. I use MPB as a generic term that encompasses bossa nova and early samba, including contemporary instrumentalists such as Egberto Gismonti and Hermetto Pascoal, and of course all the culture of songwriters that were somehow marked by the aesthetics of the Tropicalist movement.

Both Brazilian and American threads share an interest in harmonic complexity, avoiding triads or using them in fresh modal progressions. While in Jazz the emphasis of the expressive development of musical materials lies in the extended harmony that may be superimposed over traditional progressions that have been learned by memory, so as to create a safe and inspiring web of with a safe landing port so that the soloist may improvise, twisting a theme introduced by the rhythm section. Thus the omnipresence of the ii-V progression, of variations on the blues and rhythm changes progression. Of course there are great North American composers who expanded the song form to it’s limits, with unpredictable modulations and extended forms. Names such as Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus and Thelonius Monk made an impression on many ears south of the Ecuador. Their music resonated with the local sensibility. Yet in Jazz the emphasis of depth of artistic expression remains in the meaningful and always fresh thread of live improvisation.

In the Brazilian tradition improvisation plays a somewhat smaller role. Often short solos that bridge vocal sections, even in contemporary instrumental music that is heavily influenced by Jazz the space for improvisation is somewhat smaller. The most successful instrumental albums seem to be the ones where seemingly improvised moments are in fact fully notated. An excellent example of this reinterpretation of apparent relaxed musical setting is the work of Moacyr Santos, where many of the apparently improvised solos are in fact fully notated.

The instrumental scene, although important in Brazil, occupied a space that was dominated by the songwriting practice that derived from bossa nova the need for harmonic invention and a standard of word painting over sophisticated poetry full of alliterations and instances of musical choices of vowels that take precedence over meaning or that may engender new and interesting poetic meanings.

The post bossa-nova scene surrounding Chico Buaque, Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil had to deal with expectations of a high standard of musical craft. They were guitar players and, with the exception of Gilberto Gil, who was classically trained in the accordion, they were all informally trained, by ear.

Jobim was a pianist. He could have succeeded internationally as a symphonic composer if he had not been seduced by the expressive power of the popular song at the hight the bossa nova movement. Next to him we find the personality of João Gilberto, a guitar player and singer who defined the sound of bossa and created the signature whispered voice of the style, dramatically opposed to the belcanto inflected vocal style of samba, prevalent till then. His guitar style also determined the approach to the accompaniment of the Brazilian song after that.

The instrument became the core of the accompaniment for vocalists, notwithstanding its appearances as a solo instrument responsible for both melody and harmony. Throughout the development of the Brazilian popular guitar, the treatment of the instrument developed from fixed chord positions that may be linked through diatonic and chromatic bass lines to a fully malleable palette where the six strings are treated as six (or less) independent voices that may be contrapuntally treated with a freedom that progressively increases, as new intervallic combinations are constantly pursued, for originality and as a sign of sophistication. When we get to the musical universe of Guinga, we may see the vocal line navigating a tapestry of harmony inside the guitar that is at the same time fresh and contrapuntally intricate.

I limit this text to a small number of composers, as the purpose of this is not to give an account of the variety of the music produced. The purpose here is simply to draw a picture of interconnecting story lines that also have a connection with the technical and artistic development of Brazilian music in general, as it reflects the cultural background.

The Samba Parade as Opera

It is not mere coincidence that the first opera ever was performed as part of the Carnival celebration in Renascence Florence.

[more soon]

Joãosinho Trinta was a notorious Brazilian director of parades for Samba Schools in Rio de Janeiro Brazil (carnavalesco). Perhaps the single person who changed the aesthetics of the main carnival Parade in Rio a few times during the 80’s. Joãosinho Trinta introduced a standard for the extraordinary wealth of exuberance in the costumes and he enlarged the scenery, creating new dimensions of visual impact in the main parade. He is famous for his reply to critics: “Only intellectuals like poverty, the poor people like luxury.”

His style was soon to be copied by all other competing Schools of Samba. In 1989 he revolutionized the parade a second time, when he called attention to the operatic element of Carnival and brought to the Avenue Marques de Sapucai a parade that was void of any shining element and used the aesthetic of trash to print an unprecedented image in the history of the event. The parade of Samba School Beija Flor that year marks a historic shift in the evolution of the genre. The strongest image of the parade was the Christ, a tourist landmark in Rio that would have been represented as a gigantic beggar, but due to a prohibition articulated by the Catholic church ended up parading under a veil of black plastic, which made the shape even darker and the social statement stronger.

There’s much opera in MPB

The dramatic song setting of Noel Rosa and Chico Buarque.

The urban poetry of Noel provided the frame for dramatic portraits that pierced the heart of a new audience that was learning how to interact with the modern phenomenon of radio and the microphone. Noel gave shape to the developed samba-song, a refined work of art that borrowed its melodic nuances from the organic intonations of current spoken Portuguese. It was a specific form that offered a new freedom, but also the challenge of a highly sophisticated art with the potential to reach to a large audience, spread through a continental nation that shares much in this one language. Chico would pick up on Noel’s legacy, added by the harmonic sophistication and high art legitimacy that bossa nova had created. The bossa nova generation stands between Noel and Chico, Noel was slightly younger than Villa Lobos and grew up in a time when the music of Carlos Gomes was being reevaluated and was still performed.

Chico could be said to be the Brazilian Shakespeare. There is much that connects both artists, especially in the dramatic quality, in the refined polish of the language, but most of all because both found words that would become meaningful and memorable for both the intellectual elite and the common folk. I claim that the dramatic quality of opera remains dormant underlining much of the popular songs that shaped the cultural scenario of Brazil thought the 60s and the 70s and to some extent passed on to a lineage of new artists.

Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil both have a similar place in the pantheon of great modern songwriters to emerge out of bossa nova. Yet, their poetry overflows in personal lyricism and chronicles of cultural struggles, reporters of metaphysical considerations. They represent the tradition of the bard, the songwriter as a commentator and inspired observer of reality. Their iconic friendship that transpires love and affection in its purest form, made into a product of the media in a time when the concept of the pop start was still somewhat naive and allowed for legitimate transgression. The mixed shades of their skin colors traduced the most positive images that Brazilians like to associate with ourselves. They offer heart-felt criticism of our own shams and in their attitude as public figures, they prefigure an example of what we could look like as a nation, and much of what is best of our affectionate culture.

Yet the drama that Caetano and Gil offer us is not of an operatic nature. Chico Buarque managed to build his lyricism on a persona that never overexposed the artist, as much as that would be possible, under the scrutiny of the local press for decades. Yet Chico protects his private inner core under a shy performer with a humble attitude and a poetic delivery that is full of characters. He manages to give complete dramas with full arch of development and resolution of conflict, all within the rigid constrains of a 4 minute radio-friendly song.

Of course, Chico Buarque is not just a songwriter, he is a prize-winning prose writer, and a poet about whom many academic treatises have been written. He was also successful in the musical theater genre, out of which came many of his most memorable songs, like Gota d’Agua and Barbara. Among many Brazilians, the most beloved songwriters in a country of songwriters, in the Golden years of Brazilian song. He even wrote the “Opera do Malandro”, which is operatic in its absurd story, although structurally molded as musical comedy. At the end the composer presents the audience with a string of famous opera arias, with rewritten words. There is a cultural statement about European culture in contrast with our popular forms and yet a sign that the composer was fully aware of the Italian and Germanic traditions. He is capable of quoting and making satire of it.

______________________________________________________________________________

There’s more, coming soon.

Also check:

Scene by Scene:

Plastic Flowers – Monodrama.

…

You must be logged in to post a comment.