Mourning for Nelson Mandela, I think about how I have always been interested to know more about South Africa. There are many places in the world that I would like to visit. However, my musical instincts keep making me think about South Africa, for the vocal tradition and for the history of using music as a tool for social transformation.

I was born and raised in the capital of Brazil. Early in life, I had an interest in music, which led me to the local music school. I also had an interest in the rhythms of popular music. I participated in ceremonies of the Afro-Brazilian religion Candomblé. I played hand drums on Friday evenings. I was privy to insights into the spiritual nature of music.

At the same time I marveled at the development of western classical music and delighted in my father’s record collection, diving into Bach, Debussy, Mahler… As a teenager, I navigated European twentieth century music. I led a double life: fascinated by atonality during the day and enchanted by popular music of all sorts at night. These were distant worlds that I tried to reconcile with modest means, in my own music and poetry. Punk rock gave me permission to be a musician, Bossa-Nova taught me how to be a self-contained artist with my voice and a guitar. Eventually I found a path to opera, a medium where I could dispose of a wide vocabulary to express emotional contrast and drama. Opera was an uncharted territory, a place where the tradition was so old and stale that the horizon of what can be done is fascinating. Everything I heard was so museum-like that I felt that the world of opera needed someone like me: a free spirit with the courage to bring some groove and new life into the music.

This has been a gratifying path that led me to my voice as a composer. Yet my recent exposure to South African music brought me further epiphanies. When I first saw the documentary Amandla! A Revolution in Four-Part Harmony I was taken by the powerful use of the human voice in these communities and the freedom to improvise in harmony. I started researching South African artists and listened to a variety of records. I cannot understand the words, but something in this music touches a core of me, influencing my production since.

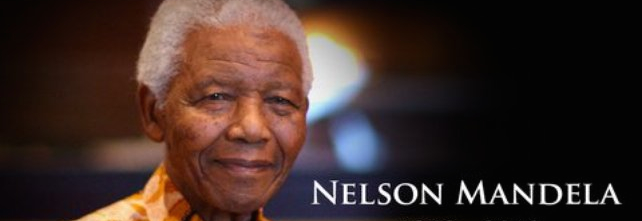

The figure of Nelson Mandela looms large above the planet, someone who set an example for all of us, someone who pointed to a path of pride, love and reconciliation. South Africa is a country with many similarities to Brazil, yet it has a distinct history with dramatic moments of struggle and redemption. It is particularly insightful the way which South Africans have tried to come to terms with their past and the atrocities of the apartheid years. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission set an example for humanity of forgiveness and tolerance even in the face of the most terrible crimes. Nelson Mandela led a path that reconciled opposite points of view. This may yet shed light into a path to a wider cultural crisis that seems to have spread across the Western mode of thinking.

I am not a politician. I am just a musician and a composer. Yet I can see how the example set forth by the spirit of Mandela in South Africa could serve as an inspiration for all creative artists of our time. And maybe we can help shape the consciousness of new politicians to come.

In hindsight, it seems natural that European music arrived at the devastation of atonality early in the twentieth century. The century that brought us the possibility of total annihilation in the atomic bomb has its musical picture beautifully portrayed in the sparse sounds of Webern’s serialism. The meaningless of the war machine has its definitive portrait in the violence of Berg’s Wozzeck.

However, how do we continue life after all the past has been deconstructed? How do we sing when we need to make a choice between hope and despair? Boulez and Babbitt were possibly right about progress in music. Yet what exactly does this notion of progress entitle? And where did it lead the civilization that invested so much in it? Should we build greater and more powerful bombs, since we can? What is the responsibility of the artist in this moment when we face a choice between ignoring that the planet is melting under greenhouse gasses or trying to save it somehow?

Idealized exotic innocence can no longer be aimed at. We will not give up the comforts of consumerism, or the connectivity of satellites. We need to figure through our common experience what to do with this legacy, how to build a path of hope for the future. Music has always set the tone of its time. Composers are the bearers for the vision of their culture.

South Africa is an example of understanding to the world. It may as well set the tone for new music that may be relevant today. Recently I saw Charles Hazlewood’s: U-Carmen eKhayelitsha. This powerful rendition of Bizet’s opera, infused with South African reality and vocal color, brought tears to my eyes. It made me think of my journey, seeking a compositional path that may blend the variety of influences that shaped the musician that I am. This is a place that I would like to visit and breathe the wisdom of their people.

Thank you Nelson Mandela, tonight I light a candle for you, to have a blessed journey to the next place. Tonight I light a candle for you, in thankfulness for all the wisdom that you poured into the planet. Tonight I light a candle for Nelson Mandela, in the hope that your smile will resonate through the world, like the powerful notes of a major chord, sung by the beautiful voices of South African women.